Basics of RWH || RWH from Rooftop || RWH Illustrations || Ground Water Recharge || RWH - Roads, Parks, Layouts

|

Rainwater Harvesting (RWH) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Articles Published in leading News Papers / Journals

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

http://www.thebetterindia.com/92434/a-r-shivakumar-rainwater-harvesting-bengaluru-karnataka/ * ~ * ~ * * ~ * ~ * http://www.theweek.in/columns/guest-columns/we-dont-respect-water.html * ~ * ~ *

|

|

Sl. No. |

Topic |

Date of publication |

|

|

1. |

25 July 2011 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

2. |

1 August 2011 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. |

8 August 2011 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. |

15 August 2011 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. |

22 August 2012 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

6. |

29 August 2011 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

7. |

5 September 2011 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

8. |

12 September 2011 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

9. |

19 September 2011 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

10. |

10 October 2011 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

11. |

17 October 2011 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

12. |

24 October 2011 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

13. |

31 October 2011 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

14. |

7 November 2011 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

15. |

14 November 2011 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

16. |

21 November 2011 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

17. |

28 November 2011 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

18. |

05 December 2011 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

19. |

12 December 2011 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

20. |

19 December 2011 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

21. |

2 January 2012 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

22. |

9 January 2012 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

23. |

16 January 2012 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

24. |

23 January 2012 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

25. |

30 January 2012 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

26. |

6 February 2012 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

27. |

13 February 2012 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

28. |

27 February 2012 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

29. |

5 March 2012 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

30. |

12 March 2012 |

![]()

Rainwater harvesting : Holds Water

The man behind rainwater harvesting projects in Bangalore

Edition: December 27, 2012

A.R. Shivakumar's inventions have made rainwater harvesting more efficient Photo: Deepak G . Pawar

It is a familiar scene during summers in many urban areas. A municipal water tanker trundles into a neighbourhood, which has not received water in its taps for days. A mass of people promptly converge on it carrying buckets , pitchers, drums - anything that can carry water. While the rest queue up, amid much jostling, a few athletic types clamber on to the top of the tanker and send water down using rubber pipes.

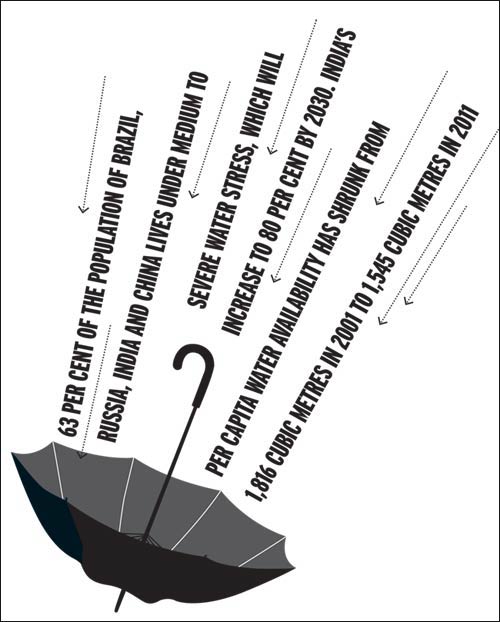

It happens because there is just not enough water available for India's 1.2 billion and growing population. An Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report titled Environmental Outlook to 2030 says 63 per cent of the population in Brazil, Russia, India and China are living under medium to severe water stress, which will increase to 80 per cent by 2030. Already, India's per capita water availability has shrunk from 1,816 cubic metres in 2001 to 1,545 cubic metres in 2011, according to the latest census.

But the situation can be turned around. "At present, water is being wasted or mismanaged," says A.R. Shivakumar, 52, senior scientist at the Karnataka State Council of Science and Technology (KSCST), a Bangalorebased government body. A vociferous proponent of rainwater harvesting - capturing, purifying and storing rainwater in large tanks - he has invented tools that simplify the process and has even got local authorities to make rainwater harvesting compulsory in the heart of Bangalore.

Shivakumar started with his own house, which he built in 1995. The rainwater harvesting apparatus collects more than 200,000 litres of rainwater a year in three storage tanks, that hold a total capacity of 45,000 litres. Naturally, he collects most of the water during the rainy season - May to October. But it is enough to sustain his family's needs - including potable water - even during the dry season. Indeed, he has not taken any external water connection at all.

As opposed to the usual sandbed filter, Shivakumar has devised and patented a PopUp filter that can be vertically installed on the wall of a small building to remove impurities before rainwater is collected. For buildings that are bigger, he developed a 'First Flush Lock and Diverter' which does the same.

If the tank collecting rainwater overflows, the excess water is discharged into the ground through a barrel system, another Shivakumar invention, which has even been named after him. The system is now being propagated in Africa, as well as in some developed countries, by the Norwegian government, which had a joint project with India on environment conservation.

Since 2002, Shivakumar has designed and executed hundreds of rainwater harvesting projects in Bangalore, including at the landmark Vidhana Soudha, the Karnataka High Court and office buildings of private companies such as Intel India and Arvind Mills.

The main source of potable water for Bangalore is the river Cauvery, which is available at best for two to three hours a day. Rainfall, about 97 cm a year, is higher than in other landlocked areas such as Delhi but lower than in coastal towns. With the city's population swelling, ground water levels have shrunk. "A couple of decades ago, water was available at 10 to 15 feet below the ground," says Shivakumar. "A few years ago, most of these wells went dry and new borewells failed as water was not available even at 800 feet in some places."

At Shivakumar's persuasion, in 2009, the Karnataka government passed an amendment to the Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB) Act. The amended Act made rainwater harvesting compulsory for home and offices with an area of more than 2,400 sq. ft. in the heart of Bangalore. So far, of the 60,000 buildings there with BWSSB water connections, more than 43,000 have adopted harvesting techniques.

"Our housing society with 95 units has now completely stopped buying water from private players," says Suraj Raheja, a resident of a housing society on Ali Askar Road, Bangalore.

A few states such as Delhi, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu had brought in rainwater harvesting legislation even before Karnataka, and a number of others have since also done so, either across the entire state, or in select cities. "All states should go in for such mandatory legislations. Only then can we beat the scarcity," says Shivakumar.

- Sebastian P.T.

By Anita Hamilton Monday, Oct. 03, 2011

A six-month drought, China's worst in 50 years,

has devastated crops and drinking water supplies.

Photo Credit: Hao Tongqian Xinhua/Eyevine/Redux

Record droughts have parched the earth's crust from Somalia to Texas this year. The effects on the world's drinking-water supply have been enormous. The level of China's Yangtze River, the third largest in the world, sank so low this spring that about 400,000 people along its shores were stuck without a local drinking-water source until the government opened the gates of its massive Three Gorges dam to help counteract the crisis. In East Africa, some 10 million people have been punished by the region's worst drought in 60 years. And in Texas, where wildfires scorched 4 million acres (1.6 million hectares) this summer, the financial losses from starving cattle and blighted crops have reached $5 billion.

Things will likely get worse. According to a new report from McKinsey, by 2030, global water supplies will meet just 60% of the total demand. Meanwhile, we'll spend an estimated $50 billion to $60 billion per year trying to bridge that gap. But while water scarcity is real, it's not happening because we have any less than we did a century ago. "We have the same amount of water," says James Famiglietti, a professor of earth-system science and civil engineering at the University of California at Irvine. But we have 250% more people drinking it. What's more, climate change means that water is "moving around to different places, even as populations are growing," notes Famiglietti. The result is not only a shortage but also a mismatch between where water is and where it's needed.

In the past, we beat water shortages by drilling for groundwater, building dams and erecting massive pipelines. But the enormousness of the problem today demands radical solutions that promote conservation as well as boost supply. "One of the reasons we have been so wasteful in the past is because it has been so easy to find another source of water," says Peter Gleick of the Pacific Institute. "But those days are over."

Novel ideas abound. In the Punjab region of India, for example, 6,500 rice and wheat farmers are testing out a $7 device called a tensiometer that analyzes ground moisture in order to prevent overwatering crops. In 2010, farmers using the tensiometer cut their water use by 22%. The trial, sponsored by PepsiCo and Columbia Water Center, will expand to some 50,000 farmers by 2012. Since agriculture accounts for 70% of global water consumption, a large-scale rollout of such devices could create massive savings.

While no single solution makes sense everywhere because of differences in climate, geography and local politics, a few are gaining traction. The best strategy often involves combining several tactics. Here are five smart ways that communities around the globe are fighting back against water scarcity:

1 Tackling the toilet-to-tap taboo Windhoek, Namibia

The idea of drinking water that was once in your toilet bowl may seem like a bad joke, but it's not. Stripped of its impurities and rigorously tested to ensure its safety, reclaimed water is one of the most inexpensive and reliable supplies of water on earth. "This is where we have to use our rational brains to overcome our natural aversion," says Alex Prud'homme, author of The Ripple Effect. In Namibia, the driest country south of the Sahara, such recycled water accounts for 35% of the drinking supply in the country's capital city of Windhoek.

Located some 5,000 ft. (1,500 m) above sea level and surrounded by mountains, Windhoek receives a paltry amount of precipitation--just 14 in. (36 cm) a year on average--which quickly evaporates in the region's hot, windy clime. Although Namibia sits on the western Atlantic, Windhoek is too high for desalination to be feasible and too far from big rivers to the north and south to build expensive pipelines to them. So this fast-growing city first turned to wastewater processing in 1968 when local reservoirs began running dry. Upgraded in 2002, the New Goreangab Water Reclamation Plant, which cost about $16 million to build, now delivers 2 billion gal. (7.6 billion L) of water a year to the city's more than 300,000 residents, who use it for everything from drinking to bathing.

Forced through a series

of sand and carbon filters as well as ultrafine membranes--some with pores

less than one-hundredth the width of a human hair--before being chlorinated

and tested for impurities, the treated water is then blended with freshwater

piped in from a network of three different reservoirs in a 35%-to-65% ratio.

The process is 37% cheaper than pumping in water from distant reservoirs,

and the recycled wastewater costs the city less than two-tenths of a penny a

gallon to treat.

The economics are persuading many to put aside their prejudices. In 2008,

Orange County, California, began treating about 70 million gal. (265 million

L) of sewage water that it then pours into its underground aquifers.

Meanwhile, Zimbabwe's capital city of Harare will begin recycling some 21

million gal. (79 million L) of wastewater a day by 2014 for use as drinking

water.

2 Success with seawater desalination Perth, Australia

Most of our planet's surface is covered by oceans, so finding a way to turn our salty seas into something palatable is an obvious solution. Desalination, which typically involves using high pressure to force water through membranes that keep the brine behind, has become increasingly popular, with more than 15,000 desalination plants churning out about 17 billion gal. (64 billion L) of freshwater a day.

One place where desal makes sense is Perth (pop. 1.7 million), the largest city in Western Australia. With daytime watering bans firmly in place and most homeowners already collecting rainwater in backyard barrels to hydrate their gardens, Western Australia's capital city turned to desal in 2007 as a drought-proof insurance policy when water levels in dams dipped to less than a quarter of their maximum capacity.

Today, a third of Perth's 96 billion-gal. (363 billion L) annual water supply comes from government-owned desalination plants in nearby Kwinana and Binningup. By the end of 2012, half the city's freshwater will come from the two plants, which will be powered by renewable-energy credits from wind and solar farms. Households will pay an extra $50 on top of their average annual bill of $700 to cover building and maintenance costs for the additional supply.

Desal is no cure-all. Even as the technology has taken off in much of Australia, Israel and the Persian Gulf, residents in some coastal communities in California, for example, are balking at the costs, which can be up to five times more than for wastewater recycling.

But new measures to reduce desalination's ecological impact, combined with smart thinking on how to lower the costs of powering the plants, are making desalination much easier to swallow. In July, Siemens announced that it had successfully tested a new desalination technique called electrodialysis that mimics the human kidney's electrochemical filtering process and uses less than half the power of traditional desalination methods.

3 Mandating rainwater harvesting Bangalore, India

Water scarcity is a problem not just in desert climates. Even Bangalore, in southern India, which gets more than 38 in. (97 cm) of rain a year and is nicknamed the Garden City for its lush, hilly terrain, has been rationing tap water for its 9.5 million residents in recent years. The population has increased nearly 50% since 2001, thanks to an influx of workers to the city, the heart of India's Silicon Valley. Now half of Bangalore's 2,00,000 wells--which account for some 40% of the city's water supply--have gone dry, and running water is available only two to three hours a day. Shortages have become so bad that some people use bottled water for bathing or buy tanks of it from privately run trucks that drive around town when the city taps shut down.

In 2009, when Bangalore's water supply fell 25% below the estimated 112 billion gal. (424 billion L) needed each year, the city finally resorted to mandatory rainwater collection on both commercial and residential plots larger than 2,400 sq. ft. (223 sq m). In less than two years, half of the 60,000 households covered by the order began harvesting rainwater on their properties.

Those who have complied have done so without a government subsidy of any sort, even though a typical setup costs about $500. That rate of compliance can be attributed to government threats to cut off the water supply, a rather draconian stick. To ease the transition, the state has set up educational fairs, trained 1,300 plumbers and developed low-cost, compact filters to replace the larger, less effective sandpits used in other areas of the country. In addition, the city plans to offer a 2% property-tax rebate for those who comply by the end of the year. With the program expanding to smaller plots as well as all commercial and government buildings, A.R. Shivakumar, one of the program's architects, hopes that 40% of the city's water supply will come from rainwater harvesting within the next few years.

4 Incentivizing conservation Albuquerque, New Mexico

Graced with an abundance of freshwater resources, Americans have long been the poster children for water gluttony, consuming an estimated 147 gal. (556 L) of water per person per day--several times more per person than their counterparts across the pond in England. But even water hogs can change their ways: Albuquerque (pop. 550,000), once one of the most wasteful cities in the U.S., has decreased its per capita water use 38%--from 251 gal. (950 L) to 175 gal. (662 L) per person per day--since 1995, in large part by handing out more than $14 million in rebates for everything from low-flow toilets to more climate-friendly landscaping. With just 9 in. (23 cm) of rain per year on average, Albuquerque, the largest city in New Mexico, had long gulped down massive amounts of water for outdoor landscaping. As recently as the 1980s, lawns were actually required for residential plots, despite that fact that the city is located on the northern edge of the Chihuahuan Desert. But since 1996, Albuquerque's water authority has been paying residents 75 cents per square foot (7 cents /sq m) to rip out their thirsty lawns and replace them with native plants that need little water to thrive. To date, some 6 million sq. ft. (557,000 sq m) of turf has been replaced with agave plants, Joshua trees, hyacinths and other desert-appropriate vegetation in a style known as xeriscaping, which has taken off everywhere from Las Vegas to San Antonio.

To get consumers to cut back indoors, Albuquerque has instituted another set of rebates, including $200 off the price of low-flow toilets, $75 for waterless urinals, and $100 off high-efficiency washing machines. The city even pays residents $20 each to attend classes on conservation. "The most effective thing we do is educate our customers," says Albuquerque's water-conservation manager, Katherine Yuhas.

Fines and rate hikes play a key role in that education. Since 1995 the city has brought in $1 million in fines, which are levied on homeowners who let water run off their property or turn on sprinklers between 11 a.m. and 7 p.m. from April to October. A new rate hike set to kick in next year will increase residential customers' bills by about $3 a month, for a total price increase of 154% since 1995. That may sound extreme, but some think the price of water should be even higher. "If you compare the price of water with the price of gasoline, it is grossly underpriced," notes Upmanu Lall, director of Columbia Water Center.

The city's mostly gentle nudging has paid off. Since 1994, Albuquerque has saved more than 100 billion gal. (380 billion L) of water. That's a three-year supply.

5 Closing the water loop, Singapore

The world leader in water conservation is arguably the tiny island nation of Singapore. Smaller than New York City and packed with some 6 million residents, this economic powerhouse located just north of the equator gets plenty of rain but has little room to store it. Its densely populated terrain and sandy soil don't hold groundwater. As a result, Singapore has had to import up to 40% of the 380 million gal. (1.4 billion L) of water it uses each day from neighboring Malaysia, from which it gained political independence in 1965.

To achieve its goal of water independence before 2061, when its contract with Malaysia expires, Singapore has moved fast to exploit new technologies, promote conservation and ensure that every drop of water used is also recycled.

The Singapore solution has four main "faucets." First, 17 reservoirs, many of which were created by damming rivers, collect the nation's 100 in. (254 cm) of annual rainfall. Second, all rain that flows into the city sewers gets recycled as drinking water. Third, the county desalinates water from the surrounding seas to supply another 10% of its drinking water. Most impressive, however, is Singapore's $3 billion wastewater-recycling system, which channels all water from toilets and other household uses into a 30-mile (48 km) underground tunnel, then sends it out to four water-recycling plants that use reverse osmosis and ultraviolet light for purification. This water is not reused for drinking but instead gets piped to the island's silicon-wafer plants for use in their water-intensive manufacturing process. The recycled water is also used to cool commercial air-conditioning systems in the country's many high-rise buildings.

The government's tiered pricing structure penalizes those who use too much water. Use of dual-flush toilets (which vary the amount of water per flush for liquid or solid waste) and other efficient appliances is strongly encouraged.

"They've become the world's ultimate water conservationists," notes Cynthia Barnett, author of Blue Revolution, a new book on water scarcity. In 2010, Singaporeans used just 41 gal. (155 L) of water per person per day--a fraction of that consumed by Americans--all while enjoying one of the highest standards of living on earth. Even the city's many reservoirs double as water parks, where boating and other aquatic sports can be enjoyed by all. It's real-world proof that conservation doesn't have to mean deprivation.

Wednesday 9 September 2009

Homing in on

green truths

http://www.deccanherald.com/content/23196/homing-green-truths.html#top

Eco friendly homes : The inventions and innovations of scientist A R Shivakumar not only make his house amazingly eco-friendly, but are inspiring thousands of schools, homes and offices where these award-winning measures are being implemented, says Aruna Chandaraju

For scientist

A R Shivakumar and his family, ecofriendliness is a way of life. And it is

showing the way to others too. Sourabha, their family home, is truly

extraordinary.

From the past 14 years, it is 100 per cent self-sufficient in terms of water

resources including drinking water, and has no municipal connection. It

draws water from a depth of 30 ft in an area where the groundwater norm is

250-300 ft. It uses just 80 units of power monthly for a four-member family;

boasts of natural airconditioning; zero-bacteria drinking water without

waterfilters; a biodiverse environment; and is cockroach-free, etc.

Shivakumar has perfected a range of award-winning eco-friendly measures and

inventions for this. He is Executive Secretary, KSCST, Indian Institute of

Science (IISc), Bangalore; and provides technical support to the world's

biggest rainwater-harvesting project.

Groundwater recharge

Total water self-sufficiency is achieved through rainwater harvesting and

groundwater recharge using a pop-up filter and barrel system, both his

inventions.

With Bangalore receiving about 1,000 mm rainfall annually, his 2,400-sq-ft

plot receives 2.4 lakh litres.

And not a drop is allowed to run outside. Sourabha has an overall

45,000-litre storage capacity - the rest is discharged into the earth via Shivakumar's (named after him) barrel system of groundwater recharge.

He has also rejected conventional steel pipes to save energy loss from

friction and used instead single-piece HDPE pipes. Before the water flows

underground, it passes through the pop-up filter which removes large

impurities.

The filter can pop up and release extra water in case of excess flow or

filter getting choked when the family is away. We are offered water by

Shivakumar's wife Suma, herself engaged in greening the colony by planting

saplings and herbal plants, from a jug containing a silver foil. They

explain this innovation: "We get pure drinking water from rain water without

using electricity, chemicals or water filters. Collect raw water in a clean,

closed container for a day's requirement (eight to 10 litres per family per

day) and immerse in it a pure-silver foil (10 by 30 cm) or wire for eight

hours.

The water is 100 per cent bacteria-free, has no side-effects, and the foil

doesn't impart any taste or odour to the water."

The other power savers are a solar cooker and a right-door refrigerator.

Shivakumar removed the hinges and reversed the door direction, thus,

right-handers keep the door open for less time, saving power, since power

used by a fridge is directly proportionally to the time its door is kept

open.

Solar energy

Solar energy panels on the terrace provide hot water for bathrooms through a

low-wattage, high-efficiency water heater with a paddy husk insulator, an

invention that fetched Shivakumar a national award for New Innovations.

Solar energy also powers most bulbs; the rest are CFLs. The skylights in the

home-centre, two of which also serve as ventilators, and profusion of

enormous windows and glass doors provide natural illumination during

daytime.

The fans are rarely used thanks to a natural air-conditioning system

achieved through: (a) Windrose diagram. The wind direction in the plot is

gauged and doors and windows constructed to guide the wind along the 'Green

Curtain' i.e plants/trees and waterbodies around the home. These filter the

air since greenery absorbs carbon dioxide and deposits moisture. Thus, only

fresh, clean and cool air enters the home. (b) Laurie_Baker inspired

rat-trap design for walls wherein bricks are placed with three-inch gaps in

between, which act as insulation.

Fewer bricks

This design also consumes 40 per cent less bricks. And these are high

quality bricks, so no plastering and painting were needed on the outer

walls. Non-plastering saves 50 per cent of cement costs. Benches in rooms

are in natural stone, the cheapest option for seaters and also maintenance

free.

The window grills and house gate are of powder-coated bright steel bars

which require no painting.

On split levels

Sourabha is located on an incline of nearly seven feet on the northern tip.

To benefit from this topography and avoid cost and effort of excavations and

fillings, Shivakumar built Sourabha on split levels.

The home has a white roof so heat gets reflected away in summer. "Experts at IIS have proved that 62 per cent of a home's heat comes from the roof. With

this trick, the figure becomes 17 per cent," he explains. The

heat-contributing south and west walls have been made blind with bright

paints while the north and east directions have maximum doors and expansive

windows which together with skylights ensure full air circulation and

diffused light. A neem tree serves as a natural pesticide for the profusion

of greenery including the terrace garden, all organic.

Shivakumar's family doesn't use the municipal garbage bin-plastic / metals

generated are given to ragpickers for recycling, and organic waste deposited

in vermicompost pits to generate organic manure.

He's even kept out cockroaches. And wouldn't every housewife love to know

how! "A little research revealed they generally don't breed in homes but

mainly in the municipal sewerage pipe, and enter homes by crawling through

connecting pipes which each home has with that master pipe. So, I broke the

existing connecting pipe and built, instead, one with a U-shaped tube (water

trap) which doesn't allow cockroaches to crawl through."

For all the scientific innovations, there has been no overlooking design

aesthetics in the process.

The home is well-designed and elegantly accessorised too.

* ~ * ~ *

![]()

CURRENT SCIENCE, VOL. 92, NO. 2, 25 JANUARY 2007, PAGE 161

World's largest rainwater harvesting project in Karnataka

http://www.ias.ac.in/currsci/jan252007/contents.htm

Click on this link to view the pdf file

* ~ * ~ *

![]()

Spectrum

Tuesday, September 5, 2006

Page I

The power of an individual

If

the environment around us is still a bit friendly, despite it being heartlessly

polluted and looted of its rich wealth, it is because of a few people like Mr A

R Shivakumar, a Senior

Scientist and Principal Investigator-RWH since November 1981, at the Karnataka

State Council for Science and Technology, situated in the lush green campus of

the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore.

This humble Engineer is an innovative thinker who has been fascinated by the power of science in making our lives comfortable as also preserving nature. No wonder he won the National Award for Invention of the High Efficiency Low Wattage Electric Water Heater from the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India, in the year 2002.

His list of inventions is quite long starting with the Sisal Decorticator, which he developed as part of his final BE project in 1981 and won the State Science Council award. This design of Mr. Shivakumar was later adopted as the national design and today thousands of farmers across the country are using this simple machine to separate the fibre from the sisal plant locally, to avoid transportation costs and improve the efficiency. He was one of the scientists, who advocated the popular energy saving ASTRA stove and worked for its dissemination to remote villages. He then improved the design of bullock carts to suit the unfriendly roads of the villages, invented the low cost eco-friendly, solar godowns to dry coconuts within 6-7 months, coconut frond shredders for optimum use of dry fronds and so many other small things to help the rural sector.

These innovations apart, Mr. Shivakumar's contribution to rainwater harvesting is something that needs to be stressed upon. His house "Sourabha" is a place every Bangalorean "must" visit. Adopting all the points he propounds, Mr.Shivakumar saves nearly nearly 30-40per cent power and managing without availing the Corporation water facility! His family of four is able to manage all domestic needs, including gardening, washing the car, etc. with the rainwater they collect in their sump for nearly eight to nine months a year. For the rest of the year, they pump water from their borewell, which is also well recharged with rainwater by direct injection, through infiltration gallery.

His simple and cheap eco-friendly roof integrated solar water heater, designing of rat-trap walls, simple water purifier, which needs no power, solar cooker, solar lighting and adoption of very simple methods like painting the terrace white, strategic placement of windows and doors and having water bodies and greenery all around have all helped the family save power to a major extent. Added advantage is that the members remain in the pink of health.

But Mr Shivakumar's knowledge is not restricted to benefiting family. He wants to help the State in which he lives as much as possible and has been toiling for this with pleasure. He was the principal instigator of the first ever structured pogramme on RWH under the Indo-Norwegian Project in 2002. This was a Rs.50-lac project interestingly born at Mr.Shivakumar's house, which impressed the Norwegian Councillor very much.

Ten Demonstration Plots were taken up and they were Vidhana Soudha, High Court, GPO and Mail Motor Service, GKVK, Fire Station, Rajajinagar, Kengeri Beedi Workers' Housing Colony, Kidwai Memorial Hospital, Collegiate Public Instructions, KSCST and the BMP buildings. Besides, two exhibition plots at Banshankari BWSSB Service Station and the BMP Day Care Centre at Richmond Town were also taken up.

"Working on this project was a very fulfilling experience. Each building is a marvel in its own and I can write a book about this project. For instance, when we took up the High Court building and went on to the roof top to look for the drain pipes from there, we were astounded to find none all around the building. We had to research a lot to realise that the pipes were embedded inside the lovely red pillars of the building. What a wonderful way of hiding those ugly pipes.

Mr A R Shivakumar.

"Then, coming to Vidhana Soudha, executing the RWH project was a challenge because we were given strict orders that the beauty of the building should not be marred in any way. After a lot of thinking and planning, we had to bring the rainwater outside the building through ventilators of the five feet thick walls in the basement.

"My BMP project was also very interesting. Just as I entered the BMP office, I found the old swimming pool being demolished. I rushed to the Commissioner and requested him to stop that work immediately, because that pool was a wonderful, huge tank, where lakhs of litres of rainwater could be stored. The Commissioner was very cooperative and today, you can see a lovely landscape above the pool and below it is stored all the water, which meets the needs of the BMP office for the whole year.

Low wattage heater.

"At GKVK, we have executed a zero-discharge project, which ensures that not even a drop of water goes waste", says Mr Shivakumar.

Mr Shivakumar has conducted 26 training programmes for different target groups like the architects, builders, contractors, plumbers, service providers, planners and policy makers, IAS, IPS and IFS officers. He also fondly remembers his active participation in the Government of India, Department of Science and Technology funded project in Tumkur, where too, ten public buildings such as the Government Hospital, DC's Office, SIT, etc. were taken up for implementing RWH schemes.

Mr V P Balegar, IAS was very supportive in setting up quasi-Government Rainwater Resource Centres in each District and also implementing the RWH project at least in a minimum of 20 houses in each village of every taluk, covering all the 176 Taluks of Karnataka, he says. The personnel in these district centres will be trained and attached to the local Engineering College.

"Arghyam", a voluntary organisation under the leadership of Ms.Rohini Nilakeni will extend its support to monitoring all the activities in the rural RWH programme.

Mr Shivakumar goes all out to see that RWH is adopted by as many Bangaloreans as possible and hence participates in a number of Radio and TV programmes to give publicity to this essential concept.

Besides, Mr.Shivakumar has published "Amruthavarshini" a guide for RWH in Kannada & English. He has also published a number of articles and papers on the topic individually as also in cooperation with his colleagues. He has been instrumental in providing technical support and specifications for RWH in the Government Schools of Karnataka. The RWH team of the KSCST consisting of enthusiasts like Mr.Shivakumar visit various districts in the State for advising and guiding the field level implementation of team for installation of RWH in 23000 23683 rural schools.

Coconut frond shredder.

"Karnataka Vikasa" the Government of Karnataka journal, has extensively covered the experiences and success stories of the various RWH projects in the State.

Apart from his pet project of RWH, Mr Shivakumar fondly remembers his success story when he was on a 6-year deputation to International Energy Initiative for Energy Planning and Conservation, where he worked for a project on Sustainable Energy Supply funded by the Rockfeller Foundation.

"It was a very rich experience. I realised the strength of involving communities in self governance. Our country really needs many such projects, because the Government cannot meet the needs of all the remote villages with its limited funds and infrastructure. I was the Programme Executive for Asia Office.

"Under that project, we had chosen ten villages and set up low-cost community bio-gas plants. We used to ask the farmers to deposit cattle dung at the plants every morning and paid them 5 paise per kilogram for dung transfer. They were permitted to take back an equal quantity of used up dung, which was now more enriched and served as better manure for their farms. A pass book was maintained to keep note of the dung deposited and taken back. With a simple bio-gas engine, electricity was produced under the supervision of just a local attendant. This power was supplied to all houses. Each house was provided with one tube light point and a tap.

"The same engine used to produce electricity during the night and pump water to the houses during the day. Each family had to spend just Rs.10 per month. towards maintenance of the engine and salary of the attendant. The project took off very well and the people too were very happy, as they received water and power at their doorsteps at such a minimum cost. The villages almost became self sufficient and did not bother about the electricity supply not reaching their villages.

"However, it is sad that in a few years, due to various obvious reasons, the projects started fizzling out in the villages. Today, Mavinakere village alone continues to successfully operate this bio-gas plant. The Mahila Sangha runs the unit under the supervision of BAIF (Bharatia Agro Industries Foundation). Such models should be publicised more if all the villages in India are to progress soon," says Mr. Shivakumar.

This world will be a much better place if each one of us is as motivated as Mr. Shivakumar to conserve energy, water and protecting the eco-system.

* ~ * ~ *

|

|

Homing in on green truthsEco friendly homes : The inventions and innovations of scientist A R Shivakumar not only make his house amazingly eco-friendly, but are inspiring thousands of schools, homes and offices where these award-winning measures are being implemented, says Aruna Chandaraju http://www.deccanherald.com/content/23196/homing-green-truths.html |

|

|

afddf